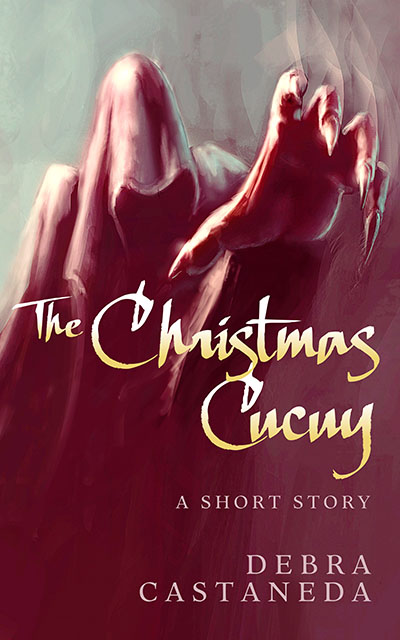

The Christmas Cucuy

La Loma, Chavez Ravine, December 1949

If that son of hers didn’t behave, and fast, she’d never finish making her new dress. And if she didn’t finish, who knew what she’d wear in front of all those people at the Palladium on Christmas Eve? A woman like her didn’t have a closet full of fancy gowns to choose from. She didn’t even have a closet, just a rickety wardrobe she shared with her husband, Henry. At least their tiny bedroom had a view. The window faced Elysian Park, its long row of trees spiking the gray December sky.

The four-room clapboard house they’d bought with the last dollar in their savings account sat tucked away among the hills of La Loma, high above the bustling streets of Los Angeles. At first, the isolation had filled Kiki Fonseca with unease. She’d grown up in the nearby village of Bishop, closer to downtown. But she’d come to love her home, which sometimes felt like it was in another country—her own—and she cherished the rolling hills, the grazing goats, the sound of men whistling their way home after a long day at work, voices echoing across the ravine.

If Henry were home, he could help get the kids in line. But without him, she couldn’t think straight. Not with Rudy chasing Cora around the house, pretending he was the boogeyman.

Sometimes, Kiki marveled at how easily she’d traded her dream of singing in a band for two kids and a mortgage. After she’d met Henry, one thing followed another.

But now she had a chance. An unexpected, early Christmas gift.

Of course, she felt bad when she heard a car accident had sent the singer of her old band to the hospital, but as the bandleader said, “You’d be doing us a real favor, Kiki, if you can do this. And everyone will get to hear that beautiful voice of yours again.”

But as soon as she told her family the big news, it seemed as if they had conspired to ruin it for her. Her mother was suddenly too sick to babysit. Henry accepted double shifts at the hospital where he worked as an orderly, and he was only home to sleep and eat. Henry’s parents took off for Oaxaca, for who knew how long. Fortunately, her sister had taken the kids to her house in Palo Verde so Kiki could work on her dress in peace, but after a few hours, she heard the front gate slam open and feet pound up the steps.

“What happened?” she asked her sister, hands on her hips, as Rudy shoved past her into the house.

Sally, her younger sister and newly married, sagged against the porch railing, holding Cora on her hip. “Ai, Kiki, I don’t know how you do it. I told Rudy we were going to feed the chickens, but he went running off with some boys and when I finally found him, they were sliding down that hill up near the police academy on pieces of cardboard and of course he got all messed up with a cactus. I tried to fix him up, but he wouldn’t let me.”

Cora burst into tears. “I told him not to, Mama. But he was bad.”

Kiki spent the next half hour smearing iodine over the wounds while her son screamed. He only calmed down after the reddened holes had disappeared under the layers of gauze, held closed with masking tape.

With a wistful glance at the dark green satin draped over the Singer sewing machine, she made the kids a quick lunch of quesadillas, then ordered them to their bedroom to nap. It was the only way she was going to finish her dress.

Cora fell asleep right away, a chubby hand balled up and pressed against her mouth.

“I’m not a baby anymore, mom,” Rudy bellowed. “Only babies take naps.” If he kept hollering like that, he’d wake up Cora.

“Fine,” she snapped. “But you’re being punished for being such a bad boy and not listening to Tia Sally. You lay there for an hour, and then you can get up.” With an hour, she could finish the sleeves and maybe even start on the hem.

Rudy’s heels drummed the bed. “That’s stupid. I don’t want to just lay here.”

Kiki clutched the door and said a little prayer to El Santo Niño de Atocha, begging for patience. Or wisdom. Anything to help her deal with this child who was beautiful, but troublesome. He’d been an easy baby, but by the time he started walking, he’d given up naps, refused to get dressed in the mornings, climbed where he shouldn’t, and at the age of six, still threw the occasional temper tantrum. And he didn’t tire easily, so she never got a break. She loved him. Loved him so much. The way his big brown eyes looked up at her. The way his black hair fell over his forehead. His skin as radiant as bronze, his lips as red and sweet as the statue of El Santo Niño himself. And he was smart. So, so smart. That’s what his teachers said.

“But he’s as stubborn as they come,” Mrs. Roberts warned one day after school. “You better learn to control that child because he’s got you wrapped around his little finger.”

Which was exactly what Henry said. But she didn’t have the heart to spank Rudy. And sometimes it was just easier to let him have his way because she dreaded his tantrums.

And then, an idea popped into her head.

Rudy,” she said sternly. “If you don’t behave, do you know what’s going to happen to you?”

Rudy propped himself up on an elbow and blinked. “No. What?”

“The cucuy is going to come get you. You know who that is right? The boogeyman. And believe you me Rudy, you don’t ever want to mess with the cucuy. He’s got big teeth and real long nails, and he grabs up all the naughty children before Christmas, then throws them into his sack and takes them away.”

Rudy’s eyes widened. “What does he do to the little children?”

Kiki could see his lower lip had started to tremble and felt a flicker of guilt. But she pushed it aside. Her green dress was waiting, and she was running out of time. She had less than twenty-four hours to finish it, plus there were dozens of tamales to make. She and her sister would be up until all hours getting them done so Sally could deliver them in the morning to a market in Boyle Heights. In return, Sally had promised to babysit the kids while she was performing at the Palladium. At her age, she wasn’t about to get another chance to sing with such a popular band, and she needed to look glamorous.

So, she said, “Not just little children, Rudy. Bigger kids too. Like you. All the naughty ones who won’t listen to their mommies and daddies and tias.”

When he scrunched his nose and opened his mouth like he was about to argue, she added, “I’ll tell you what the cucuy does to children. He drinks their blood and eats them with his big, long teeth. Do you understand, Rudy?”

His nostrils flared, and he bit his lip. “I guess,” he muttered, then rolled over and faced the wall.

She hovered in the doorway, twisting her hands, half expecting him to pop up like one of those jack-in-the-boxes she’d hated as a child. But after a few minutes, his wiry body relaxed, and she could tell from his breathing he was drifting off to sleep.

Kiki closed the door quietly and tiptoed into the living room. Working quickly, just like she had in her old job as a seamstress, Kiki sewed in the cap sleeves—biting her lip during the tricky turns—added a few pleats and managed a decent, straight hem. Without the kids constantly interrupting, she easily finished the dress, and when she glanced up at the clock on the wall, she realized nearly two hours had slipped by.

El Santa Niño must have heard her prayers. Nothing else could account for Rudy sleeping so long in the middle of the day.

She was in the kitchen making coffee when Cora dashed in, arms stretched out in front of her, face twisted in terror. “Mama! Rudy says he’s the cucuy and he’s going to drink my blood.”

Kiki snatched up her daughter and glared at Rudy. “You stop that right now if you know what’s good for you, mister. Don’t you be mean to your little sister.”

Rudy made a face and rubbed his knee. “You were mean to me. You said the cucuy was going to get me.” That was the thing about Rudy. The boy always had a comeback.

“Don’t you listen to him,” she whispered into her daughter’s ear, stroking her soft cheek.

Rudy stomped a foot, then banged out the screen door to the back porch, where he kicked a metal pail down the steps. Clang. Clang. Clang.

“Stay in the backyard, Rudy,” she shouted. The last thing she needed was to chase him all over La Loma. He liked nothing better than wandering the open hills, returning covered in dust after hours of rough play.

A few minutes later, he began tormenting Cora again. That time, he got more creative. He grabbed an old blanket, draped it around his head and shoulders, then opened his mouth as wide as it would go and jumped out from behind the sofa, shrieking, “Bwah hah hah” at Cora. She suffered such a susto that Kiki had to give her sips of warm water mixed with sugar to revive her.

Kiki had had enough. She ordered Rudy out of the house. “And don’t come back until you’ve decided to behave yourself, young man,” she shouted after him as he raced away down the street. He hadn’t even bothered to answer. Rudy had simply flapped his hand over his head as if to say, Yeah, yeah.

Rudy still hadn’t come home when her sister, Sally, her husband, Bill, and a few of his friends from Palo Verde arrived for a night of tamale making. They didn’t have a phone, so there was no way Henry could call her, but she guessed he was working straight through. Sometimes he did that. He punched out an hour earlier that way.

It was dark out—although not past five-thirty—when Bill said, “Do you want me to go look for Rudy?” She was about to reply (“Oh please, would you?”) when she spotted a dark shape crossing the backyard, and she heaved a sigh of relief.

When Rudy trudged into the kitchen, reeking of little boy sweat, she said as nonchalantly as she could, ‘Oh look who decided to finally come home.”

Rudy gave her a long look, rushed toward her, then threw his hands around her waist and buried his face in her stomach. This unexpected show of affection filled her with alarm. “What’s wrong, mijo,” she asked. “Did something happen?”

“No,” he said, voice muffled. “Nothing happened. I just missed you. That’s all.”

Kelly looked up from smearing masa onto a corn husk. “Que milagro,” she said. Kiki agreed. Her son showing affection was a miracle, and not one she was about to waste.

“I missed you too, mijo.” She cupped his sweet, pointed chin in her hand and tilted his head until their eyes met. “And I love you. Very, very much.”

“And you won’t let the cucuy get me?” he whispered.

“Ai no,” she said, then marched him to the sink and washed his hands in hot water with Lifebuoy soap.

For once, Rudy sat quietly through dinner—tamales pulled steaming hot from the giant pot bubbling on the stove—along with rice and beans. Her brother-in-law, a real sweetheart, gave the kids a bath and she could hear them splashing and laughing down the hall.

The fellows from Palo Verde had brought some beer and a bottle of red wine for the ladies, and after a few small glasses, Kiki was tipsy enough that she agreed to model the green dress she’d made to wear on stage at the Palladium. Then, after Bill had wrestled Rudy and Cora into their pajamas and then into bed, he ducked out onto the front porch, danced back in carrying a guitar, and demanded Kiki sing a few songs. Years ago, before she’d got married, they’d belonged to the same Latin band with the name they still laughed about: “Pachuco Suave.”

Kiki climbed on top of a chair and while Bill strummed, she belted out a song. When she was done, her eyes shone, Kelly clapped her hands, and the guys from Palo Verde whistled.

“The people are going to love you,” Bill said, grinning.

Kiki heard a noise at the kitchen door, and when she turned, saw Rudy standing there, scowling. “Why are you doing that?” he demanded. “Are you going somewhere?”

Kiki and her sister exchanged glances. Bill crossed the kitchen in a few steps and picked up Rudy. Her son went stiff as a washboard and pulled his head back as if his uncle had bad breath. “I’m not little. Put me down.”

Instead, Bill sank into the closest chair, his big arms wrapped around Rudy’s tiny waist. “Now listen, nephew. You be nice to your mama. You know she’s going to get to sing at a big fancy place tomorrow. That’s why she’s been working so hard on that real pretty dress. Now, doesn’t your mama sing beautiful? Aren’t you proud of her?”

Rudy shook his head so hard his wet hair fell in front of his eyes. “No. No I don’t want my mama to sing in front of people. She’s my mama. And that’s a stupid dress. She needs to stay home with me and Cora. We can’t stay by ourselves.”

“Ai, Rudy, listen to you,” Bill said with a laugh. “You know you’re staying with us tomorrow at our house. We just talked about it during bath time.”

But Rudy still acted as if she were abandoning them, and soon Cora stumbled into the kitchen, rubbing her eyes, and began whining too. The kids cried and carried on for the rest of the tamale making. Bill’s friends slinked out early, muttering excuses about a house party in Bishop, and when her sister and brother-in-law finally got up with tired sighs, Kiki could tell they couldn’t wait to leave either.

Kiki eyed the clock, wishing her husband would get home to help settle down the kids. Rudy listened to him. Mostly. She wondered if Henry had gone out to a bar. Not that she’d hold it against him. He was a good husband and father and rarely went out with the guys.

By ten o’clock, Cora had collapsed into bed, exhausted. With a two-hour nap, Rudy’s eyes were still bright, and alert and he moved with a frightening energy, following her every move, saying, “Please, please, please don’t leave me tomorrow night mommy,” and when he noticed she was still wearing the shiny green dress, he began tugging at it as if to rip it from her body.

She pushed him away and said, “You stop that right this second, young man” in such a hard voice he took a step back in surprise. But that didn’t stop him for long. He shuffled his feet and wiggled his hands around the top of his head like a bull, then charged, ramming into her so hard she fell back onto the sofa.

When she finally sat up, stunned, and sputtering with fury, she pointed a trembling finger at him and screeched, “That is enough, Rudy Fonseca. Do you hear me? Enough. I’m calling the cucuy right now and if you don’t go to your room this second, he’s going to come, and you are going to be sorry. And I mean really, really sorry.”

Rudy didn’t budge. He stood in the center of the tiny living room, between the old easy chair and the side table covered with a lace doily. When he shrugged, Kiki could hear her heartbeat pound in her ears and her breathing came out noisy and wrong.

Her black shoes—the ones she’d polished for her big night at The Palladium—smacked against the hardwood floor. Panting, she clacked across the room and flung open the front door. It was dark outside, the dirt road empty. La Loma, like the two other rural villages of Palo Verde and Bishop, were dark and lonely at this hour. Tomorrow would be different, on Christmas Eve, when families and friends would get together for parties, lights blazing, music blaring. But not her. She’d be singing her heart out at the Palladium. If that child of hers would ever calm down so she could think about the music, the lyrics, and how she would move her body on stage.

Her back to Rudy, she waved her hands in front of her as if trying to flag down a car. “Cucuy? Do you hear me? My son has been a bad boy. A very bad boy. You have my permission to come and get him.”

She glanced over her shoulder. Rudy was biting his lip, but he gave another shrug, as if daring her to say more. She was in a battle of wills with that stubborn child of hers, and for once, she wasn’t about to lose. Kiki raised her foot, then brought the heel down with a satisfying crack, like the small pistol Henry used to shoot tin cans.

Once again, she turned to the door. “Do you hear me out there, Cucuy? I’ve got a naughty boy here who needs to be taught a lesson. Because he sure as heck is not listening to his mother.” Lips pressed into a straight line, she once again looked over at Rudy, who scowled in the glow of the table lamp.

With legs planted wide, he said, “I don’t care. You can’t scare me. And you’re a mentirosa. Uncle Bill said there’s no such thing as the boogeyman.”

That was just too much to take. Her son, her six-year-old child, had called her a liar. His own mother, a liar. Well, she’d show him.

Shaking with indignation, she whirled around and shouted, “Okay, Mr. Cucuy. That’s it. I’ve had it. If you want him, you can have him. His name is Rudy Fonseca and if you decide to add him to your list of bad little boys, I’m not going to stop you. Come and get him, Mister Cucuy!” She thought that last bit was a nice touch.

In the distance, a coyote howled.

“Mama,” Rudy whispered. “Did you hear that?”

She sighed, shoulders sagging with fatigue. “It’s just a coyote. We hear them every night.” But there was something different about that one. It went on longer, louder. Like a warning.

Her eyes remained fixed on the road. Suddenly, the wind picked up. Even in the darkness, she could see the dirt lift from the ground, pebbles too, swirling in the air. Specks of dust circled the lone bulb on the front porch. She coughed as the musty earthiness reached her nose.

Behind her, she could hear Rudy creeping forward. “Stay back,” she said, flapping her hand at him, her voice high and shrill.

She was about to shut the door when a terrible howl pierced the night air. The sound made her blood run cold. That was no coyote. The coyotes that loped through the ravines at night were skinny. Whatever made that awful noise sounded like a much bigger, scarier animal.

Her throat went dry, and her fingers clenched the door as she squinted in the general direction of the noise. It was coming from up the road, where it ended at a barren hill. There was nothing up there but an old well and some weeds.

The fearful noise moved closer at an astonishing speed, hurtling toward them, the sound of it rattling chain-link fences. Pails and washbasins hummed. Withered vines toppled from the sides of sheds.

“Mother of God,” Kiki whispered. Her feet had grown roots, fixing her to the floor. Her legs threatened to stop holding her up.

It was coming. Whatever it was, it was almost there.

Kiki could feel the night air grow colder. So cold she could feel her nose and cheeks burn, like when she once played in the snow at Big Bear. Powerless to move, she watched as a giant shadow filled her vision, stopping on the road in front of her house, its form taking shape. A towering figure in a hooded cloak. Kiki wanted to look away, but her eyes seemed determined to confront the thing, which was gliding toward her, slowly now, as if it had all the time in the world. The hood covered its face, but not enough to hide its red eyes and too many yellow teeth.

Her throat had gone so dry it took the greatest effort to speak. “Run, Rudy,” she croaked.

But the shadowy monster was too fast. Something hit her shoulder hard, then she felt herself flying. When she crashed into a wall with a thud that rattled her teeth, she saw the creature yank Rudy off the ground with hands that glowed a sickly white, its nails filthy and tinged with red. She watched, bile rising in her throat, as her son’s little body disappeared into a sack. The demon stopped to consider her a moment with its red eyes before throwing the sack over a humped, deformed shoulder.

The table lamp flickered on and off. It was enough to rouse Kiki, and she scrambled on all fours toward the hideous monster. It paused at the front door with its head cocked to the side, as if puzzled by the fuss. Then it shrugged and disappeared into the night, Rudy’s muffled shrieks fading.

Somehow, she found enough strength in her legs to stand. She stumbled to the front porch. She pulled herself along the railing, lurching down the steep stairs and into the empty road. The closest house was not too far, and she ran there, hands stretched out in front of her, as if she could catch the monster that had stolen her son.

And then she remembered Cora, still asleep in her bed.

Kiki retraced her steps, a hand pressed against her lips to keep from screaming. She flung open the door to the bedroom, slamming it against the wall, and Cora sat up with a shriek. Kiki smothered her with kisses and a stream of, “Thank God, thank God, thank God,” before snatching her from the warm sheets.

“Mama, what’s happening?” cried the little girl.

Kiki grabbed a blanket from the bed, wrapped it around her daughter’s tiny body, and once again fled down the road. Terrified, Cora buried her head into her mother’s neck, and when the door of her closest neighbor’s house opened, Anna Garcia’s startled face appeared in the gap.

“Madre mia de Dios, Kiki. Are you okay? What’s wrong?”

Kiki shook her head. There was no time to explain. She shoved Cora at the woman who’d been her closest neighbor for the last six years. “Just watch her for me. Please. I need to go. Rudy’s gone. Missing.”

Anna gasped. “What do you mean missing?” She absently stroked Cora’s hair, damp from sleep, as she looked over her shoulder into the house. “Gus. Get out here now. Something’s happened to Rudy.”

Gus appeared by his wife’s side a few moments later, wearing a thick jacket and carrying a flashlight. He shot a worried glance at Cora, who had begun to cry. Loud and pitiful wails of confusion and fright. “It’s okay, mija. We’re going to find your brother.”

Knowing Cora was in good hands—praying that whatever had taken Rudy would not return to take her baby too—she ran toward the road, hardly knowing where she was going. She only knew she had to find the cucuy. She made it as far as the bottom of the hill, falling several times. Each time, Gus hauled her to her feet, and she continued, ignoring his onslaught of questions. Finally, he grabbed her by the shoulders and forced her to stop.

“Listen to me, Kiki. I need to know what happened. Where did you see him last? What time?”

She shook her head and cried, “You don’t understand, Gus. The cucuy took him. I saw it. It came to my house, and I couldn’t stop it. I tried, but I couldn’t. And now Rudy’s gone, and I don’t know where. You’ve got to help me.”

Gus took a step back. “Have you been drinking, Kiki? Because that’s one helluva crazy story.”

Kiki grabbed the lapels of his jacket and shook him. “It’s not a story Gus,” she sobbed. “It happened. It was the cucuy. I swear it.”

Gus cleared his throat. “Ai, Kiki. I think you’re hysterical or something. The boogeyman is just a story. But bad men? They kidnap children all right. We need to call the police, and right away. Let them do their job and find him.”

Kiki blinked, considering his words with what little part of her brain that still worked. If the police came, that would mean more people looking for Rudy. People trained to search for missing children. But in her heart, she knew they would never find him, even if they believed her story about a tall, hooded stranger with nails like claws.

“You don’t really think it’s the cucuy, do you Kiks?” Gus asked, shuffling his feet.

She pressed a hand against her mouth to stifle the scream rising in her throat, and managed to choke out, “Yes, Gus. Yes. I saw it.”

Gus nodded, gripped her elbow. “Okay, Kiks. This is what we’re going to do. I’m going to the Medina’s house to call the police on their phone, but first I’m walking you to Lencha’s. Because if it’s the cucuy who took your kid, then she’s the one you really want.”

Kiki felt her toes curl in her shoes. She’d seen the curandera around. She was a fixture in the community, making cures for the sick. But in all the years she’d lived in Loma, she’d chosen to take Rudy and Cora to the healer in Palo Verde, even though Lencha was closer. There was something about the woman’s dark and steady gaze that made her nervous, as if she could see right through her. Also, Lencha had a reputation as a bruja, and while she commanded respect, Kiki preferred to keep her distance. But tonight, she was desperate. And if the cucuy had Rudy in its clutches, then only a witch could help him now.

Buoyed with the faintest flicker of hope, they ran all the way to Lencha’s house. The curandera opened the door with a scowl, a shawl draped over her flannel robe. “Whatever it is, this can’t be good,” she said in a flat voice, then she motioned them inside.

Gus tipped his head, turned on his heel, and bounded down the path to the street, the beam of his flashlight swinging wildly. Now that she was there in the company of the bruja, it felt like cotton filled her mouth. What would she say to this woman? How would she find the words to explain what happened?

Lencha sighed, pulled her across the small and tidy living room, then pushed her into the kitchen. The room smelled of cinnamon, sugar, and butter. Kiki collapsed into the closest chair, buried her face in her hands and sobbed.

Silently, Lencha busied herself at the stove as Kiki cried herself out. When Kiki raised her head, tears raining down her face, the curandera slid a steaming mug in front of her, fragrant with chocolate.

“Drink it,” Lencha ordered, her face as still as a mask. Kiki did. The taste of whisky overpowered the chocolate, and she felt the hot liquid slide down her throat.

It was cold in Lencha’s house, even with the oven on. Then again, after the cucuy, all the warmth had drained out of her, and her bones felt icy and brittle.

Lencha hurried from the room and returned a few moments later carrying a blanket draped over an arm, which she tucked around Kiki’s thin shoulders. “Are you going to tell me what happened?” Lencha asked in a sharp voice, a tone that contrasted with the gentleness of her touch.

Kiki swallowed. A numbing calmness coursed through her. The brain fog lifted, just enough, so words could form in her mouth. “The cucuy took Rudy,” she said, then waited for Lencha’s reaction. But there was none.

“Oh, did he?” Lencha finally said, shoving her hands into the pockets of her robe.

Kiki bit her lip. She was feeling woozy. “Yes. I know it’s hard to believe, but it’s true. He came and took my child. My son. He’s only six.”

Lencha sat down hard in a chair. “I believe you.”

“You do?” Kiki hadn’t known what to expect from her first conversation with the bruja, but it wasn’t this.

Lencha shrugged, flicked her long black braid over her shoulder. “I’d be a fool not to. If you say it was the cucuy, I have no reason to doubt you. But I have a question. Why did the cucuy come to your house?” She paused, crossing her arms in front of her chest. “And whatever you do, Kiki Fonseca, you tell me the truth because your son’s life depends on it. Entiendes?”

Kiki understood. “I don’t know why he came to my house.” She took another sip of hot chocolate to numb the desperation squeezing the air from her lungs.

Lencha slammed her hand on the table, rattling the sugar bowl. Kiki jumped. “Now you’re lying,” the curandera said. “Because the hasn’t stepped foot around here for years. Not since we put a spell around the whole area, from Bishop to La Loma, to keep him away. Someone let him back in, and I think it was you. Was it?”

The words dried up in Kiki’s throat. The room spun, and her breath rattled out. She sounded like a train chugging into the station. Instead of answering, she nodded and swiped at her forehead with the back of a damp hand.

Lencha sat back and studied her with cold, dark eyes. “I need to know exactly what you did. What you said. And don’t hold anything back. Not if you want to see your son again.”

Kiki got up and began pacing. The blanket slipped from her shoulders and fell to the floor. When she bent to retrieve it, she remembered she was still wearing the green satin dress—rumpled now, and ripped, the hem dusty and ragged.

“Rudy was misbehaving,” she began, avoiding Lencha’s piercing gaze. “I mean, really misbehaving. Disobeying me every chance he got.” Her voice dropped to a whisper. “So, I got the idea that I could scare him. You know. With the cucuy.”

Lencha pressed a finger between her eyes. “That’s how it always starts. And then what?”

“I opened the door and called for the cucuy,” Kiki answered through gritted teeth, then threw her head back and moaned.

“You opened the door and called for the cucuy,” Lencha repeated, shaking her head.

Kiki’s heart twisted in her chest while her stomach heaved. “I didn’t think he was real! He’s just a story to scare kids. My mom used to scare me with him all the time, but nothing ever happened.”

Lencha’s fingers drummed the table. “How many times did you call him?”

Kiki squeezed her eyes shut, thinking. Not easily done. Not with her brain running in different directions, each one ending with Rudy being carried away by a monster hungry for children. “I don’t know,” she said faintly. “Three maybe.”

Now it was Lencha’s turn to groan. “Of course. Three times. You called him three times. Well, that did the trick. You messed up our spell and you messed it up good.”

Kiki’s heart pounded, ready to explode. She threw herself at Lencha’s feet. “Don’t say that Lencha. Please don’t say that. Just tell me what to do. I’m sorry. I’m so, so sorry. Please. I’ll do anything to get him back. Anything.” Her icy fingers kneaded Lencha’s thighs. “If you put a spell on the cucuy to keep him away, you must know of a spell that can bring back my boy, right?”

Lencha’s eyes softened. She leaned forward, touching her forehead against Kiki’s, and said, “There is a way. And only one. But there will be a price to pay. He won’t let Rudy go just because we ask. If he hasn’t killed him already. He will ask for something in return, and there will be no bargaining.”

Kiki shrank back with a gasp. “Cora. You’re saying he’ll want Cora instead.”

“No,” Lencha replied, shaking her head. “He’ll want to make you pay, for wasting his time.”

“Me?”

Lencha’s dark eyes never left hers. “Yes.” The woman got to her feet, pulling Kiki along with her. “But we have to hurry.” She grabbed a lantern from a cupboard, lit it, then pushed Kiki out the back door and into the inky blackness of the night.

It was impossible to guess Lencha’s age, her skin was browned and weathered by the sun, but Kiki suspected close to forty. The curandera moved fast and sure footed, the lantern lighting their way. Kiki kicked off her high heeled shoes to keep up, fighting back another wave of tears, dizzy with desperation and fear. Her bare feet seemed to find every rock and pebble, but she hardly noticed.

They passed her house, the door wide open. The lamp in the living room glimmered behind the curtains. Lencha pulled her up the road toward the hill with the well, the stars in the night sky indifferent to their quest. The wind had kicked up, chasing away the clouds, rustling through the patches of tall scrub. Kiki sagged against the solid wooden walls of the well.

The curandera set the lantern on the uneven ground, then snatched the blanket from Kiki’s shoulders and threw it over her head. Plunged into darkness, Kiki struggled, trying to free herself of the shroud.

“Leave it,” Lencha commanded. “Whatever you do, don’t take it off until I tell you.”

Kiki felt Lencha grab her by the shoulders and give her a shake. “Kiki. Did you hear me?”

“Yes,” Kiki cried. The rough blanket scratched her cheeks and tickled her nose. But it was a small price to pay if it meant she was one step closer to getting Rudy back. She dared to hope. Later, she would remember that moment and laugh. Silently.

While she could not see, she could listen. She went still and turned her ears in every direction, her entire body stiff with the effort. Lencha was somewhere in the distance, higher on the hill, chanting in a strange language she couldn’t understand.

The air seemed to change around her, and she felt something rushing toward them. The foul smell of the cucuy announced its arrival, and then, dear mother of God, she heard the pitiful cries of a child. “Mommy. I want my mommy.”

She wanted to scream. I’m here Rudy, I’m here. But she shoved her fist into her mouth, terrified to interrupt whatever Lencha had planned.

Lencha was talking in the strange language, in her matter-of-fact voice, as if talking to a neighbor at the store and not a monster in the night. In response, she heard a low growl, then a series of wet sounding gurgles and grunts like those of an animal. But as awful as the sound was, she strained to listen. To understand.

Then the blanket was ripped from her head, and she found herself staring into the red eyes of the cucuy, who towered over her, filling her nostrils with its stench of death and decay. She cowered against the well, her eyes sliding to the monster’s sack, which wriggled on the ground at its feet, toenails curved and sharp as talons. Lencha hovered several feet away, face grim in the faint glow of the lantern.

The monster snatched up the sack and dangled it high in the air, regarding her with its red eyes, something that passed for a twisted, taunting smile on lips stretched over those horrible yellow teeth.

In a move so fast it took Kiki’s eyes seconds to catch up, the cucuy swung the sack over its head several times like a lasso, then loosened its grip. The sack, with her son in it, flew into the night, and arced down the hill, where it landed with a sickening thud. Lencha, braid flying behind her, sped down the slope while Kiki screamed—first from imagining Rudy’s broken little body, then from the pain of something piercing her right foot. When she glanced down, she saw the cucuy’s foot covered her own, a talon spearing the tender flesh between her big toe and long toe, pinning her to the ground. Blood bubbled up around the wound. Every muscle in her body ached to run to her son, but the cucuy had other plans. With a snarl, it lifted its foot, then in one swift movement, cuffed the side of her head and sent her sprawling. Head ringing, dazed, she scrabbled toward the boogeyman, who loomed several yards away, studying her like a principal would a naughty student.

“Please,” she cried. “Please. I made a mistake. I didn’t mean it. I didn’t want you to take my son. I love him. I do.”

She swiped at the tears flooding her eyes—insensible to the pain of her bloodied foot. When she forced herself to look up at the monster, she beheld another creature. A young woman with dark hair in a long, green satin dress. For a moment, all she felt was confusion, and then she understood.

The cucuy had taken on her image, but it was as misshapen and as twisted as looking into a fun house mirror.

The arms were too long and thin. Bulging in the middle. Humpbacked. Worst of all were the big, bloated lips that dominated its face. The face she’d always been told was beautiful. She couldn’t stop staring at the abomination. It minced around her, hands on its hips. The awful swollen lips moved. The cucuy was talking, and somehow, she understood.

“Do you hear me out there, Mr. Cucuy? I’ve got a naughty boy here who needs to be taught a lesson. Because he sure as heck is not listening to his mother.” The cucuy halted its mincing steps and pouted. The eyes were dark like her own, but strangely large and encircled by puffy gray flesh.

Her words. The words she shouted into the night, threatening her own son. “I didn’t mean it!” she cried. She buried her face in her hands and sobbed.

“I didn’t mean it,” mocked the cucuy. “I love him, I do.”

When she finally dropped her hands, the monster—the creature that had stolen her child and her likeness—grinned.

“But I do,” Kiki whispered. “I do.”

The cucuy made a clucking sound and resumed its exaggerated walk, swishing its hips and stepping high. Once again, the boogeyman repeated the words she regretted saying more than anything else in the world: “Okay, Mr. Cucuy. That’s it. I’ve had it. If you want him, you can have him. His name is Rudy Fonseca and if you decide to add him to your list of bad little boys, I’m not going to stop you. Come and get him, Mister Cucuy!”

The demon stopped abruptly and stared down at her, hands on his hips, just as she had done with Rudy earlier that night.

“Come and get him, Mister Cucuy!” it thundered. The ground shook beneath her, once again knocking her to the ground.

When she looked up, the boogeyman had transformed back to its original, ghastly shape. She cried out in relief, no longer faced with her ugly and distorted self, the way she must have appeared to Rudy, her own flesh and blood.

The monster sneered. “You,” it said. “You told me I could have him. You lied. Now you give me something else.”

In the distance, she could hear Rudy crying, and Lencha crooning. She wouldn’t have suspected the curandera had such a lovely voice. The cucuy hadn’t finished with them yet, but at least Rudy had survived. Relief coursed through her, so intense it weakened her tired and aching bones.

What? What would possibly satisfy the monster in exchange for her son?

She felt herself retreating, fading into numbness. A sharp slap across the face snapped her back to reality. The cucuy’s sharp nails had sliced her cheeks and she could feel the sting of it, the blood.

Give me. Give me. Give me.

But what? What did he want? If not Rudy. Or Cora. Then what?

A hand shot out from the sleeves of the tattered robe, and she recoiled, the back of her head slamming against the wood of the well. Fingernails, the color of bleached dried blood, seemed to stretch and span the gap between them. For a moment, she thought the cucuy meant to grab her by the throat, lift her off her feet, and choke her. And then a filthy fingernail pushed into her mouth, and she gagged. There was nowhere to run. Nowhere to escape. Lencha stood in the distance, her back turned, cradling Rudy in her arms like a baby.

The monster forced two fingers into her mouth, then three, and she was fighting against it as best she could, gripping its bony wrist with both hands as she whipped her head from side to side. But her strength was no match against it.

And then she remembered.

She’d promised Lencha she’d give the cucuy whatever he demanded. No bargaining. That’s what he was doing. Collecting his payment. Her arms went limp.

A twist of its bony wrist. A nail jabbing into the furthest reaches of her throat. A pain so sudden, so shocking, she passed out. When she came to, she woke to searing agony and the taste of iron in her mouth. Blood. Everywhere. She sat propped against the well, dazed, limp as a rag doll.

The monster had gone, and with it, his consolation prize.

Lencha knelt in front of her—Rudy’s head pressed firmly into her shoulder, so he could not see the horror that deformed his mother. There would be time enough for that. A lifetime. Blood pooled in Kiki’s ruined satin skirt. Christmas colors, she thought. Red and green. She would have welcomed back her son with the most beautiful words, and a song to soothe him and send him off to sleep. The song she would have sung on Christmas Eve to all those nameless faces at The Palladium, leaning forward in their seats, drinks in their hands, smiling.

If only the cucuy had not taken her tongue.