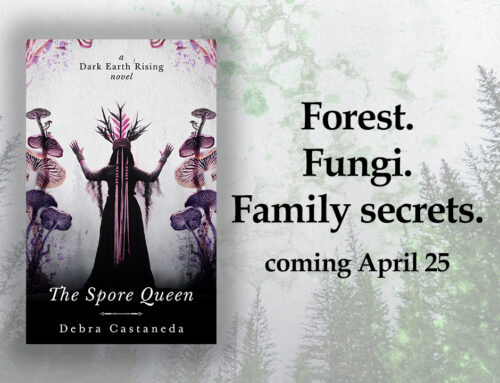

My new book is out today! The Spore Queen is a psychological, fungal horror story (some people call it “sporrer!”) featuring mystery and family secrets. But what you won’t see mentioned in the summary of The Spore Queen is brujeria, or Mexican witchcraft. It does play a part in the story, but to say anything more would be to venture into spoiler territory.

What I can say is the story explores what happens when a person is severed from their culture. In this case, that severing leads a character to create new and problematic interpretations of a craft traditionally learned over time from an experienced bruja.

I’ve featured brujeria in two of my other books: The Monsters of Chavez Ravine and The Night Lady, both set in the old Mexican neighborhoods where Dodger Stadium now stands. Palo Verde, La Loma, and Bishop may have been a streetcar ride away from downtown, but before they were razed by the City of LA, they were more like villages. Sure there were doctors (my family saw a Chinese American doctor just down the hill in Chinatown) but many residents used Mexican folk medicine to help fix what ailed them.

In both novels, a curandera (healer) named Lencha dispensed cures and eventually hechizos, or spells. Lencha’s character is based on my grandmother’s curandera friend who once gave me a red knotted bracelet to protect me against El Cucuy (the boogeyman).

In my upcoming short story, The Haunting of Chavez Ravine, Lencha will again play a central role and more of her background will be revealed.

Lencha isn’t just a curandera with dubious skills, she’s a full-blown bruja. And like other practitioners of brujeria, she is a marginalized brown woman who’s dealt with her fair share of misogyny and discrimination. The practice of Mexican magic not only empowers her but it also helps to protect members of her small community.

One of the best books I’ve read about the subject is Mexican Sorcery: A Practical Guide to Brujeria de Rancho by Laura Davila, a fifth-generation witch who learned the practice from her grandmother in Mexico. She does a wonderful job explaining that there’s no one way to practice brujeria. There are many versions, and no single belief system. The picture of Mexican witchcraft traditions is painted on a vast canvas, and the depictions in my stories represent but a small corner.

Lencha learned her skills on a rancho in Mexico before immigrating to the US. It was a way for many marginalized Mexican women to reclaim their power and individuality. Davila calls Brujeria de Rancho “a tool for rebellion; it has to do with equality, defiance, and a response to injustice and oppression.”

I always saw the characters of Lencha and Catalina (from The Night Lady) as rebels, so I was delighted to see this interpretation that supported that vision.

In her excellent book, Davila also wrote, “La Brujeria de Rancho did not incubate in the minds of occultists, nor in the lodges of the privileged; la Brujeria de Rancho had its cradle where our people suffered, sprouted from the hands of ‘powerless people,’ la gente del rancho, or people from rural areas in Mexico, the excluded and the forgotten.”

In my books, the inequality Lencha suffered in Mexico followed her to Chavez Ravine where she and the other residents were eventually forced out of their homes by the city.

So get ready for some more brujeria, when a super haunting of La Llorona (the terrifying Crying Lady of my childhood) afflicts the residents of Chavez Ravine, forcing Lencha and her niece Lily to work together to protect their neighbors against the vengeful ghost.

The story will first appear in serialized form on my author newsletter starting in May before it’s published later in the year. (Sign up for my newsletter here.)

And before you read it, you might want to find a curandera to make you a red-knotted protection bracelet!

Leave A Comment